By Spencer Davis. In the four years since Shadows & Noise launched, my year-end film picks have been all over the map: a heartfelt coming-of-age drama, a sci-fi think piece, a classic Hollywood musical. That kind of schizophrenia isn’t just a function of diverse tastes; it’s a sign of the scattershot directions in which film has been evolving in the past half-decade. With streaming supplanting the theater as our preferred way of watching, with Netflix and Amazon now acting as movie studios in their own right, and with the quality line between television and movies so blurred now that we might as well just call it all “film,” we’re at an inflection point in the history of the moving picture. Indeed, in 2017, we’re finally seeing film critics include shows like The Handmaid’s Tale, Twin Peaks: The Return, and even Ken Burns’s The Vietnam War on their year-end movie lists. But while I could easily list the likes of Legion or Mr. Robot here—shows that are every bit as cinematic and structurally innovative as anything on the big screen—I’m still limiting my picks to movies for just one reason: the difficulty of making meaningful comparisons between a finite film and a television show that is still an ongoing work in progress. It wouldn’t seem fair to list a show here that might, before it’s all over, take a major nose dive. But make no mistake, film and TV now bear equal claim to the mantle of creative greatness. So without losing sight of that, here are the twelve movies that defined my 2017.

By Spencer Davis. In the four years since Shadows & Noise launched, my year-end film picks have been all over the map: a heartfelt coming-of-age drama, a sci-fi think piece, a classic Hollywood musical. That kind of schizophrenia isn’t just a function of diverse tastes; it’s a sign of the scattershot directions in which film has been evolving in the past half-decade. With streaming supplanting the theater as our preferred way of watching, with Netflix and Amazon now acting as movie studios in their own right, and with the quality line between television and movies so blurred now that we might as well just call it all “film,” we’re at an inflection point in the history of the moving picture. Indeed, in 2017, we’re finally seeing film critics include shows like The Handmaid’s Tale, Twin Peaks: The Return, and even Ken Burns’s The Vietnam War on their year-end movie lists. But while I could easily list the likes of Legion or Mr. Robot here—shows that are every bit as cinematic and structurally innovative as anything on the big screen—I’m still limiting my picks to movies for just one reason: the difficulty of making meaningful comparisons between a finite film and a television show that is still an ongoing work in progress. It wouldn’t seem fair to list a show here that might, before it’s all over, take a major nose dive. But make no mistake, film and TV now bear equal claim to the mantle of creative greatness. So without losing sight of that, here are the twelve movies that defined my 2017.

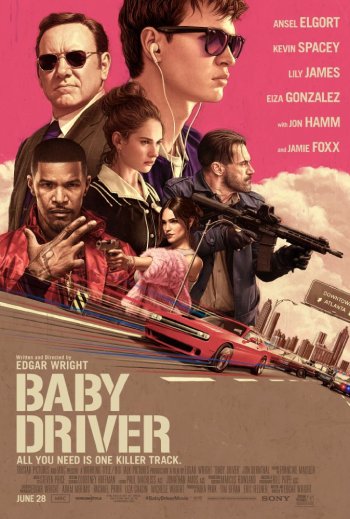

1. Baby Driver

2. The Big Sick

3. Lady Bird

4. Dunkirk

5. The Lost City Of Z

6. The Beguiled

7. Colossal

8. Marjorie Prime

9. Logan

10. It Comes At Night

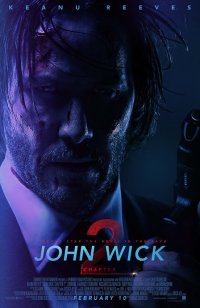

11. John Wick: Chapter Two

12. Ingrid Goes West

For a website about both music and film, Baby Driver is a natural pick for the best film of the year. No movie since, well, ever, has so intricately blended music and film into one symbiotic creation. The funny thing is that, like all works of genius, the concept seems so perfectly obvious in retrospect. Choreography is at the heart of all musicals, but it’s also at the heart of any great action movie—so why not merge the two? Ansel Elgort’s getaway driver, ears always buried between a pair of earbuds, lips always synching along, isn’t so different from the lead in any Gene Kelly or Fred Astaire movie: he’s eternally bouncing from song to song, marrying every physical movement of his body (or his car) to the soundtrack playing in the background. And what a soundtrack it is. From the Jon Spencer Blues Explosion to The Commodores to T. Rex to Dave Brubeck, his army of iPods always has the perfect track on queue. But while in real life we can only credit blind luck for those divine moments when just the right song hits your car stereo at just the right moment, in Baby Driver, the credit goes to writer and director Edgar Wright. From that first car chase onward, he stages every swerve and crash, every step and strut, every gear shift and gun shot with absolute precision—transforming the heist picture into a perverse form of modern dance. (There’s probably a statement in there somewhere about life in the Trump era, but I’ll resist). Of course, none of it would work without just the right cast, and Elgort—along with supporting players Jon Hamm, Jamie Foxx, Lily James, and um, Kevin Spacey—hits every note. Always staying on the right side of the dividing line between clever and absurd, Baby Driver fuses everything I love about movies into one exquisite piece of performance machinery.

For a website about both music and film, Baby Driver is a natural pick for the best film of the year. No movie since, well, ever, has so intricately blended music and film into one symbiotic creation. The funny thing is that, like all works of genius, the concept seems so perfectly obvious in retrospect. Choreography is at the heart of all musicals, but it’s also at the heart of any great action movie—so why not merge the two? Ansel Elgort’s getaway driver, ears always buried between a pair of earbuds, lips always synching along, isn’t so different from the lead in any Gene Kelly or Fred Astaire movie: he’s eternally bouncing from song to song, marrying every physical movement of his body (or his car) to the soundtrack playing in the background. And what a soundtrack it is. From the Jon Spencer Blues Explosion to The Commodores to T. Rex to Dave Brubeck, his army of iPods always has the perfect track on queue. But while in real life we can only credit blind luck for those divine moments when just the right song hits your car stereo at just the right moment, in Baby Driver, the credit goes to writer and director Edgar Wright. From that first car chase onward, he stages every swerve and crash, every step and strut, every gear shift and gun shot with absolute precision—transforming the heist picture into a perverse form of modern dance. (There’s probably a statement in there somewhere about life in the Trump era, but I’ll resist). Of course, none of it would work without just the right cast, and Elgort—along with supporting players Jon Hamm, Jamie Foxx, Lily James, and um, Kevin Spacey—hits every note. Always staying on the right side of the dividing line between clever and absurd, Baby Driver fuses everything I love about movies into one exquisite piece of performance machinery.

I saw an ad this year for a mediocre movie (which shall go unnamed here) that billed itself as “a romantic comedy without the bullshit.” But that description is a much better fit for The Big Sick. Part-comedy and part-tearjerker, Kumail Nanjiani’s semi-autobiographical story about the courtship of his wife, Emily, breathed new life into a cliched genre. The romance between his up-and-coming Pakistani-American comic and a white grad student (an endearing Emily Gardner) plays so naturally because it draws not just upon real experiences but real, lived-in characters. The movie truly comes alive when Emily’s parents (an Oscar-worthy Holly Hunter and a sweetly unsure Ray Romano) are forced to endure a crisis with Kumail. While the culture clash between white and Middle Eastern in this age of terrorism offers plenty of cringe-worthy laughs, its the story of Kumail’s relationship with his own family that deftly exposes the subtle bigotry that can result when immigrant families struggle with whether to hold on to the old world or embrace the new. Laugh-out-loud funny but also heartbreaking for the pain it explores, The Big Sick is as smart a romantic comedy as we’ve ever seen—and that’s no backhanded compliment.

I saw an ad this year for a mediocre movie (which shall go unnamed here) that billed itself as “a romantic comedy without the bullshit.” But that description is a much better fit for The Big Sick. Part-comedy and part-tearjerker, Kumail Nanjiani’s semi-autobiographical story about the courtship of his wife, Emily, breathed new life into a cliched genre. The romance between his up-and-coming Pakistani-American comic and a white grad student (an endearing Emily Gardner) plays so naturally because it draws not just upon real experiences but real, lived-in characters. The movie truly comes alive when Emily’s parents (an Oscar-worthy Holly Hunter and a sweetly unsure Ray Romano) are forced to endure a crisis with Kumail. While the culture clash between white and Middle Eastern in this age of terrorism offers plenty of cringe-worthy laughs, its the story of Kumail’s relationship with his own family that deftly exposes the subtle bigotry that can result when immigrant families struggle with whether to hold on to the old world or embrace the new. Laugh-out-loud funny but also heartbreaking for the pain it explores, The Big Sick is as smart a romantic comedy as we’ve ever seen—and that’s no backhanded compliment.

For the first half of Lady Bird, I wondered if I’d been the victim of some kind of massive practical joke. The rhythm of the film, the frenetic pace of Greta Gerwig’s editing and snappy dialogue, were distractingly quirky—like a self-conscious impression of Diablo Cody fueled by half a dozen espresso shots. But ten minutes after the credits rolled, my fiancee was still breaking down into tears out in the parking lot. That’s the power of the film, which sneaks up on you so slowly, letting its characters seep into your consciousness, that you don’t realize right away just how much you love it. Saoirse Ronan’s awkward coming-of-age story feels forced sometimes in its depiction of millennial affectation and detachment, but as the story slowly probes the wounds of the fractured mother/daughter relationship between Ronan and Oscar-frontrunner Laurie Metcalf, the film itself enters a kind of delayed adulthood. The payoff is totally worth it. A surefire Best Picture nominee, Lady Bird grows into something special.

For the first half of Lady Bird, I wondered if I’d been the victim of some kind of massive practical joke. The rhythm of the film, the frenetic pace of Greta Gerwig’s editing and snappy dialogue, were distractingly quirky—like a self-conscious impression of Diablo Cody fueled by half a dozen espresso shots. But ten minutes after the credits rolled, my fiancee was still breaking down into tears out in the parking lot. That’s the power of the film, which sneaks up on you so slowly, letting its characters seep into your consciousness, that you don’t realize right away just how much you love it. Saoirse Ronan’s awkward coming-of-age story feels forced sometimes in its depiction of millennial affectation and detachment, but as the story slowly probes the wounds of the fractured mother/daughter relationship between Ronan and Oscar-frontrunner Laurie Metcalf, the film itself enters a kind of delayed adulthood. The payoff is totally worth it. A surefire Best Picture nominee, Lady Bird grows into something special.

Dunkirk wasn’t what any of us expected. Of course, maybe the unexpected should be expected from a director like Christopher Nolan, who has made a career out of twisty, turny mindgames with time (Memento, Inception, Interstellar). But in Dunkirk, he created the first thoroughly-modern war movie, using three different intersecting timescapes to show the sheer magnitude of the team effort it took to rescue thousands of British soldiers in their darkest hour. For two hours, the tension never breaks as Nolan keeps turning the screws tighter and tighter (with a huge assist from Hans Zimmer’s innovative score). By the time you leave the theater, you’re physically and emotionally exhausted. Maybe it’s a bit dramatic to say this might be the first war movie that should come with a PTSD warning—but it’s probably as close as movies can come.

Dunkirk wasn’t what any of us expected. Of course, maybe the unexpected should be expected from a director like Christopher Nolan, who has made a career out of twisty, turny mindgames with time (Memento, Inception, Interstellar). But in Dunkirk, he created the first thoroughly-modern war movie, using three different intersecting timescapes to show the sheer magnitude of the team effort it took to rescue thousands of British soldiers in their darkest hour. For two hours, the tension never breaks as Nolan keeps turning the screws tighter and tighter (with a huge assist from Hans Zimmer’s innovative score). By the time you leave the theater, you’re physically and emotionally exhausted. Maybe it’s a bit dramatic to say this might be the first war movie that should come with a PTSD warning—but it’s probably as close as movies can come.

In a lot of ways, The Lost City Of Z is as much a priceless artifact of a bygone era as its titular lost city. Like Indiana Jones meets Fitzcarraldo, it recalls an era when studios still made big, sweeping epics full of adventure and mystery—without the obligatory CGI mass destruction. And yet The Lost City Of Z also breaks from the past in intriguing ways: in how it acknowledges the immoralities of colonialism and cultural appropriation; in how it takes time to explore the impact of a man’s obsessive quest for glory on his wife and children; in how it teases at the arrogant blindness with which we once viewed all of history through white eyes. As explorer Percy Fawcett’s real-life excursions into the South American jungle continue over the decades, we see a portrait of the romantic possibilities of his era—a time in which civilization was mapping out the last dark corners of the world even as the First World War was upending it. And we also see the hollowness of that romance brutally exposed, as the juxtaposition of indigenous tribes against the mechanized warfare of the “civilized world” calls into question just which of those societies deserved the title of savages. With stellar performances from Charlie Hunnam, Sienna Miller, and even Robert Pattinson, and an eyeful of beauty from director James Gray, The Lost City Of Z is a historic find.

In a lot of ways, The Lost City Of Z is as much a priceless artifact of a bygone era as its titular lost city. Like Indiana Jones meets Fitzcarraldo, it recalls an era when studios still made big, sweeping epics full of adventure and mystery—without the obligatory CGI mass destruction. And yet The Lost City Of Z also breaks from the past in intriguing ways: in how it acknowledges the immoralities of colonialism and cultural appropriation; in how it takes time to explore the impact of a man’s obsessive quest for glory on his wife and children; in how it teases at the arrogant blindness with which we once viewed all of history through white eyes. As explorer Percy Fawcett’s real-life excursions into the South American jungle continue over the decades, we see a portrait of the romantic possibilities of his era—a time in which civilization was mapping out the last dark corners of the world even as the First World War was upending it. And we also see the hollowness of that romance brutally exposed, as the juxtaposition of indigenous tribes against the mechanized warfare of the “civilized world” calls into question just which of those societies deserved the title of savages. With stellar performances from Charlie Hunnam, Sienna Miller, and even Robert Pattinson, and an eyeful of beauty from director James Gray, The Lost City Of Z is a historic find.

For a film that features so much superb female talent—Sofia Coppola, Nicole Kidman, Kirsten Dunst, Elle Fanning—it’s surprising that The Beguiled utterly fails the Bechdel test. That’s okay, because it’s still a woman’s movie through and through, even as a man (Colin Farrell) becomes the center of the universe at a small Southern boarding school during the Civil War. The presence of this injured Union solider sparks an unspoken civil war among the ladies, along with a more overt battle of the sexes—one waged with the weapons of manipulation, sexuality, and ultimately, things much deadlier. Coppola’s decision to shoot the entire movie only in natural light pays dividends as she casts her characters in silhouette and shadow—keeping the viewer in the dark at crucial moments. What The Beguiled ultimately says about the gender wars is that, like the more literal war that forms its backdrop, there’s good and bad on both sides.

For a film that features so much superb female talent—Sofia Coppola, Nicole Kidman, Kirsten Dunst, Elle Fanning—it’s surprising that The Beguiled utterly fails the Bechdel test. That’s okay, because it’s still a woman’s movie through and through, even as a man (Colin Farrell) becomes the center of the universe at a small Southern boarding school during the Civil War. The presence of this injured Union solider sparks an unspoken civil war among the ladies, along with a more overt battle of the sexes—one waged with the weapons of manipulation, sexuality, and ultimately, things much deadlier. Coppola’s decision to shoot the entire movie only in natural light pays dividends as she casts her characters in silhouette and shadow—keeping the viewer in the dark at crucial moments. What The Beguiled ultimately says about the gender wars is that, like the more literal war that forms its backdrop, there’s good and bad on both sides.

A very different kind of gender war plays out in Anne Hathaway’s quirky dramedy, Colossal. The concept requires a certain amount of buy-in: a slacker party girl on the bad end of a break-up learns that she is somehow causing a giant Godzilla-like monster to appear in Seoul each night. What at first appears like a parable about the destructive influence of alcoholism on others, though, twists into something much more timely: a morality play about how to confront toxic masculinity. In less able hands, this would be a ridiculous premise, but Hathaway sells it, and Jason Sudekis shows unexpected dramatic depth as her part-time savior and full-time enabler. Provocative without being preachy, utterly original without descending into gimmickry, the best thing about Colossal is that it convinces you that Hollywood is still capable, every now and then, of giving you something wholly new and surprising.

A very different kind of gender war plays out in Anne Hathaway’s quirky dramedy, Colossal. The concept requires a certain amount of buy-in: a slacker party girl on the bad end of a break-up learns that she is somehow causing a giant Godzilla-like monster to appear in Seoul each night. What at first appears like a parable about the destructive influence of alcoholism on others, though, twists into something much more timely: a morality play about how to confront toxic masculinity. In less able hands, this would be a ridiculous premise, but Hathaway sells it, and Jason Sudekis shows unexpected dramatic depth as her part-time savior and full-time enabler. Provocative without being preachy, utterly original without descending into gimmickry, the best thing about Colossal is that it convinces you that Hollywood is still capable, every now and then, of giving you something wholly new and surprising.

The year’s best sci-fi movie shows almost no traces of being sci-fi at all. Marjorie Prime has no flashy visuals or awe-inducing technology; the only evidence we have of the future in which it takes place is in its words. The Marjorie of the title is an elderly widow about forty years from now. She’s been given a “prime,” a holographic AI representation of her dead husband (played by a never-better Jon Hamm), who converses with her as a sort-of virtual therapist, exercising her dementia-riddled mind while he exorcises her loneliness. As with the best thoughtful sci-fi, there’s a point about humanity in all this, as the conversations between real person and prime begin to reveal the uncomfortable overlap between memories and lies—and the lengths to which we all go in writing our own life stories. Co-starring Geena Davis and Tim Robbins (in their first hefty dramatic roles in years), the minimalism of its script and direction won’t interest everyone—the action comes almost entirely through dialogue—but for those willing to sit down and just listen, Marjorie Prime will teach you a lot about yourself.

The year’s best sci-fi movie shows almost no traces of being sci-fi at all. Marjorie Prime has no flashy visuals or awe-inducing technology; the only evidence we have of the future in which it takes place is in its words. The Marjorie of the title is an elderly widow about forty years from now. She’s been given a “prime,” a holographic AI representation of her dead husband (played by a never-better Jon Hamm), who converses with her as a sort-of virtual therapist, exercising her dementia-riddled mind while he exorcises her loneliness. As with the best thoughtful sci-fi, there’s a point about humanity in all this, as the conversations between real person and prime begin to reveal the uncomfortable overlap between memories and lies—and the lengths to which we all go in writing our own life stories. Co-starring Geena Davis and Tim Robbins (in their first hefty dramatic roles in years), the minimalism of its script and direction won’t interest everyone—the action comes almost entirely through dialogue—but for those willing to sit down and just listen, Marjorie Prime will teach you a lot about yourself.

If ever there were a genre that feels like it has exhausted all its possibilities, it’s comic book movies. Yet Logan breaks through those walls to deliver a complex, adult story that just so happens to be about superheroes. The title choice signals right up front that we’re going to be seeing a more human version of Wolverine, but the true creative ingenuity of James Mangold’s film was the decision to make what is effectively a Western. By recasting Logan and Professor X as grizzled, wearied anti-heroes at the end of their days, Mangold mines a rich and familiar film language to lay bare the vulnerability that even superhumans must inevitably face as age sets in and the world passes them by. Hugh Jackman is fantastic as usual, and Patrick Stewart gives maybe the best performance of his career, expressing with mostly physical language all the pain, stubbornness, and confusion you might expect of a powerful psychic ravaged by dementia. In retrospect, it’s kind of amazing that a studio even green-lit this; after all, what’s fun about seeing your favorite heroes as shells of their former selves? But the gamble paid off big. And if the success of Logan frees blockbuster filmmakers to take bolder risks in the future, then maybe the comic book movie genre isn’t really past its prime, but just now beginning to enter it.

If ever there were a genre that feels like it has exhausted all its possibilities, it’s comic book movies. Yet Logan breaks through those walls to deliver a complex, adult story that just so happens to be about superheroes. The title choice signals right up front that we’re going to be seeing a more human version of Wolverine, but the true creative ingenuity of James Mangold’s film was the decision to make what is effectively a Western. By recasting Logan and Professor X as grizzled, wearied anti-heroes at the end of their days, Mangold mines a rich and familiar film language to lay bare the vulnerability that even superhumans must inevitably face as age sets in and the world passes them by. Hugh Jackman is fantastic as usual, and Patrick Stewart gives maybe the best performance of his career, expressing with mostly physical language all the pain, stubbornness, and confusion you might expect of a powerful psychic ravaged by dementia. In retrospect, it’s kind of amazing that a studio even green-lit this; after all, what’s fun about seeing your favorite heroes as shells of their former selves? But the gamble paid off big. And if the success of Logan frees blockbuster filmmakers to take bolder risks in the future, then maybe the comic book movie genre isn’t really past its prime, but just now beginning to enter it.

Mismarketed as a horror film, It Comes At Night suffered from the expectation that it would be something it’s not. That’s a shame, because if it had been sold as the post-apocalyptic disaster movie it really is, a lot more people might have appreciated its subtle brilliance. It’s the story of two families trying to survive together in a remote house in the woods after a plague wipes out most of society. While there isn’t really much of an “it” that comes at night, there are hints of a mysterious and deadly force out there in the forest, and visions of something demonic within—but these are only distractions from the chess match that develops between the two families when one of them potentially becomes infected. A smart and realistic take on how the dilemma of power versus compassion might play out when good people are dropped back into the state of nature, It Comes At Night rewards those who see it with a blank slate.

Mismarketed as a horror film, It Comes At Night suffered from the expectation that it would be something it’s not. That’s a shame, because if it had been sold as the post-apocalyptic disaster movie it really is, a lot more people might have appreciated its subtle brilliance. It’s the story of two families trying to survive together in a remote house in the woods after a plague wipes out most of society. While there isn’t really much of an “it” that comes at night, there are hints of a mysterious and deadly force out there in the forest, and visions of something demonic within—but these are only distractions from the chess match that develops between the two families when one of them potentially becomes infected. A smart and realistic take on how the dilemma of power versus compassion might play out when good people are dropped back into the state of nature, It Comes At Night rewards those who see it with a blank slate.

The original John Wick was one of the great under-the-radar action flicks of the past half-decade, and this year’s John Wick: Chapter Two is something rarer still: a sequel that surpasses the original. Keanu Reeves returns as a hitman pulled out of retirement against his will when his dog is killed, and director Chad Stahelski ups his game with gunfights and action sequences that are elegantly staged like ballet. Gone are the jerky, blurred, impossible-to-follow fight scenes we’ve come to expect in recent years; Stahelski lets his camera stare unblinking from a distance, allowing us to see the entire battleground unfold at once (a trick that only heightens our impressions of the badassery on display). And the script doubles down on the dignified underground society of noble assassins that Chapter One established, its ruthless killers practicing an ethical code among one another that borders on medieval chivalry. The best action franchises find a way to expand upon their world with each successive outing. After two chapters in this world, all I can say is that I can’t wait for Chapter Three.

The original John Wick was one of the great under-the-radar action flicks of the past half-decade, and this year’s John Wick: Chapter Two is something rarer still: a sequel that surpasses the original. Keanu Reeves returns as a hitman pulled out of retirement against his will when his dog is killed, and director Chad Stahelski ups his game with gunfights and action sequences that are elegantly staged like ballet. Gone are the jerky, blurred, impossible-to-follow fight scenes we’ve come to expect in recent years; Stahelski lets his camera stare unblinking from a distance, allowing us to see the entire battleground unfold at once (a trick that only heightens our impressions of the badassery on display). And the script doubles down on the dignified underground society of noble assassins that Chapter One established, its ruthless killers practicing an ethical code among one another that borders on medieval chivalry. The best action franchises find a way to expand upon their world with each successive outing. After two chapters in this world, all I can say is that I can’t wait for Chapter Three.

No less bloodthirsty is the Instagram-obsessed culture that is ruthlessly skewered in Ingrid Goes West. The story of a deranged girl (Aubrey Plaza) who takes an unhealthy interest in the perfectly-cultivated social media presence of an LA hipster (Elizabeth Olsen), it would have been way too easy for this satire of millennial priorities to descend into lazy caricature. But the script understands the world it is savaging, criticizing not from a distance but from a place of intimate familiarity—and always with an eye on the genuine human emotions that drive even the worst of online behavior. Its characters are both empathetic and pathetic, and never so easy to dismiss as we’re tempted. Just like with real social media, we cringe and yet we follow anyway.

No less bloodthirsty is the Instagram-obsessed culture that is ruthlessly skewered in Ingrid Goes West. The story of a deranged girl (Aubrey Plaza) who takes an unhealthy interest in the perfectly-cultivated social media presence of an LA hipster (Elizabeth Olsen), it would have been way too easy for this satire of millennial priorities to descend into lazy caricature. But the script understands the world it is savaging, criticizing not from a distance but from a place of intimate familiarity—and always with an eye on the genuine human emotions that drive even the worst of online behavior. Its characters are both empathetic and pathetic, and never so easy to dismiss as we’re tempted. Just like with real social media, we cringe and yet we follow anyway.

Honorable Mention:

Get Out / Wonder Woman / Logan Lucky / Mudbound / Their Finest / Frantz /

Columbus / Personal Shopper / 20th Century Women / A Quiet Passion

The Blackcoat’s Daughter / A Dark Song / Lady Macbeth / Good Time